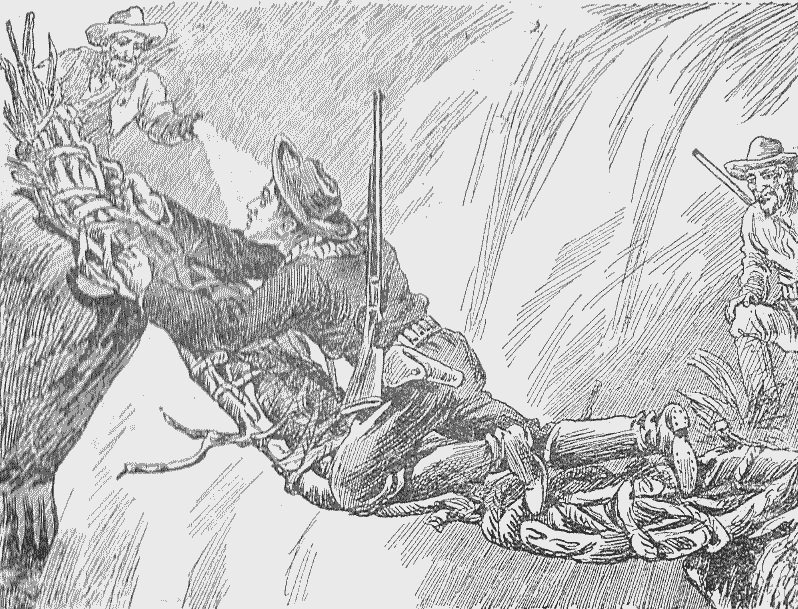

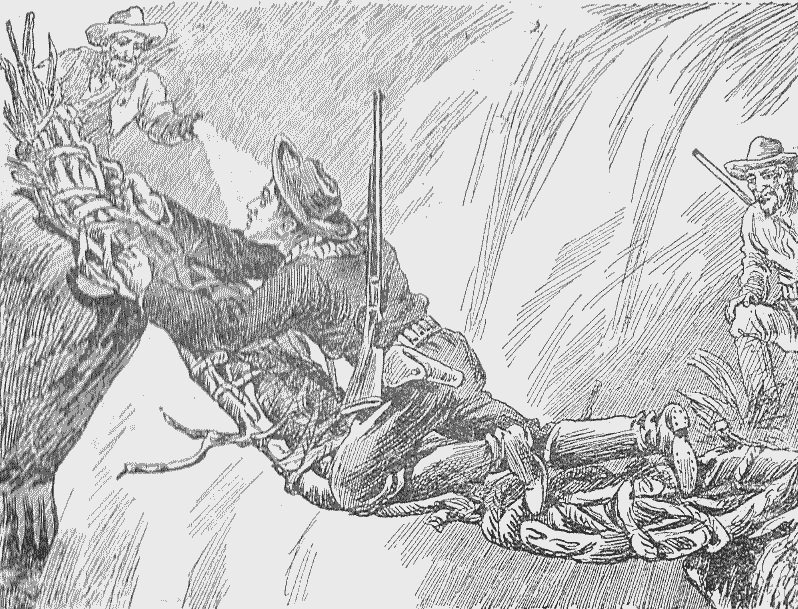

"He Placed the Ladder of Saplings Across the Abyss."

Project Gutenberg's A Desperate Chance, by Old Sleuth (Harlan P. Halsey)

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: A Desperate Chance

The Wizard Tramp's Revelation, A Thrilling Narrative

Author: Old Sleuth (Harlan P. Halsey)

Release Date: January 12, 2004 [EBook #10690]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A DESPERATE CHANCE ***

Produced by Steven desJardins and PG Distributed Proofreaders

"He Placed the Ladder of Saplings Across the Abyss."

"Well, Desmond, we've taken a desperate chance, and so far appear to be losers."

The circumstances under which the words above quoted were spoken were weird and strange. A man and a mere youth were sitting by a campfire that was blazing and crackling in a narrow gulch far away in the Rocky Mountains, days and days travel from civilization.

The circumstances that had brought them there were also very strange and unusual. Desmond Dare was the son of a widow who owned a small farm in New York State. There had been a mortgage on this farm which was about to be foreclosed when Desmond, a brave, vigorous lad, sold his only possession, a valuable colt, and determined to enter a walking match for the prize. He was on his way to the city where the match was to take place when in a belt of woods he heard a cry for help. He ran in the direction whence the cry came and found three tramps assailing a fourth man. The vigorous youth sprang to the rescue and drove the three tramps off, and was later persuaded by the man he had rescued to go with him to a rock cavern. There the lad beheld a very beautiful girl of about fourteen whose history was enveloped in a dark mystery; he also learned that the man he had rescued was known as the wizard tramp. The latter was a very strange and peculiar character, a victim of the rum habit, which had brought him away down until he became a tramp of the most pronounced type. This man, however, was really a very shrewd fellow, well educated, not only in book learning, but in the ways of the world, and seeing that Desmond had resolved to take a desperate chance, the tramp volunteered to land him a winner; he succeeded in so doing. The champion of the walking match carried his money to his mother, the tramp went upon an extended spree and spent his share. Afterward the tramp and Desmond Dare started on the road together. The girl had been placed with Mrs. Dare on the farm, and the man and boy proceeded West afoot, determined to locate a gold mine. The former discovered each day some new quality, and held forth to Desmond that some day he would make a very startling revelation. The youth had no idea as to the character of the revelation, but knowing that the tramp, named Brooks, was a very remarkable man, he anticipated a very startling denouement. After many very strange and exciting adventures Brooks, the tramp, and Desmond Dare arrived in the Rockies, and in due time started in to find their gold mine. The previous history of these two remarkable characters can be read in Nos. 90 and 91 of "OLD SLEUTH'S OWN."

At the time we introduce the tramp and Desmond Dare to our readers in this narrative, they had been knocking around the mountains in search of their mine and had met with failures on every side, and at length one night they camped in the gulch as described in our opening paragraphs, and Brooks spoke the words with which we open our narrative.

They were sitting beside their fire; both were partly attired as hunters and mountaineers, and both were well armed. Brooks, who had practically been a bloat had lived a temperate life, had enjoyed plenty of exercise in the open air, and had experienced to a certain extent a return of his original physical strength and vigor. At the time the whilom tramp made the disconsolate remark quoted, Desmond asked:

"What do you propose to do—give it up?"

"I don't know just what to do, lad."

"We've scraped together a little gold dust; possibly we may have money enough to engage in some legitimate business, and what we can't get by the discovery of a mine, we may acquire in time in speculation. You are shrewd and level-headed."

"That would be a good scheme for you, lad, but not for me. I am too far advanced in life to earn money by slow labor now. What I propose is that you go back, take all the gold we have, and enter into trade; you are bright and energetic and may succeed."

"And what will you do?"

"I shall continue my search for a mine, and some day I may strike it."

Brooks was a college graduate, a civil engineer, and a mineralogist, and believed he had great advantages in searching for a mine, but, as has been indicated, thus far their tramp and search had been a dead failure.

"I'll stick with you," said Desmond.

"No, lad, you must go back."

"I swear I will not; I like this life, and remember, we have gathered some wash dust and we may gather more. I don't know the value of what we have gathered from the bottom of that stream we struck, but I do know that it would take a long time to accumulate as much money in trade. Remember, we have been in the mountains only six weeks."

"That is all right, but we might stay here six years and not make a find."

At that instant there came a sound which caused Brooks and Desmond to bend their ears and listen. Some of the Indians were on the warpath; a band of bucks had been making a raid and had been pursued by the United States cavalry into the mountains. Indians, as a rule, do not take to the mountains, but sometimes when pursued hotly they will separate into small bands and scatter through the hills; these fellows are dangerous. They would have murdered any white men they might meet for their arms alone, without considering the spirit of wantonness or revenge that might animate them.

Brooks and Desmond rose from their seats beside the fire and moved slowly away. At any moment an arrow or even a rifle shot might come and end the life of one or both.

Desmond had become a very expert woodsman; he and Brooks had been chased by Indians several times and had exchanged shots with one band. They knew a cover in a crevice in the wall of rock which ran up abruptly each side of the gulch; from this spot they could survey and also make a good fight in an emergency. They had good weapons, plenty of ammunition, and what was more, coolness, skill, and courage. Desmond, especially, was a very cool-headed chap in times of danger; the use of firearms was not new to him, nor was the woodsman life altogether a novelty, for he had been raised in a very wild and desolate mountain region.

Quickly they stole to cover, although they believed it possible that they might have been seen, for they had absolute proof, well known to woodsmen, that if there were foes in the vicinity they had been discovered. Once in their covert they lay low, and a few moments passed, when they beheld a solitary figure advancing slowly and very cautiously up the gulch, and as the figure came in the light of the fire Desmond, whose eyesight was very keen, said:

"It's a white man; he looks like a hunter; we will wait a moment or two, but I guess it is all right."

The figure, meantime, with rifle poised, advanced very slowly and finally stood fully revealed close to the fire, and indeed he was a white man of strong and vigorous frame.

"I'll go and meet him," said Desmond; "you lay low here, rifle in hand ready to shoot in case he proves an enemy."

"All right, lad, go ahead."

Desmond stepped from his hiding-place and advanced toward the fire. The stranger saw him, still held his position ready for offense or defense, and permitted Desmond to approach, and soon he discerned that the lad was a white man and he called:

"Hail, friend!"

"Hail, to you," replied the lad.

The two men approached and shook hands. The hunter was a splendid specimen of physical manhood, and his face indicated honesty and good-nature.

"Are you alone here, lad?"

"No."

"Where's your comrade?"

Desmond made a sign, and Brooks stepped forth from the crevice and approached the fire.

"Hail, friend," said the stranger hunter.

Brooks answered the salutation, the two men shook hands and the stranger said;

"What may be your business out here?"

"We'll talk of that later on; but, stranger, you took great chances."

"I did?"

"Yes."

"How?"

"In approaching the fire you were exposed; suppose the fire had been kindled by Indians?"

The woodsman laughed, and said:

"I knew it was not an Indian's fire."

"You did?"

"Yes."

"How is that?"

"They don't create such a big blaze. I knew white men were around, and men whom I need not fear, but I was on my guard all the same."

"We could have dropped you off."

"Well, yes, but out here we have to take chances, and it was necessary for me to do so."

"It was?"

"Yes."

"How so?"

"I need food; I have not struck any game lately. The fact is, I've been up in the peaks where there is no game. I hope you have a cold snack here, my friends, and some tobacco, for I have not had a regular tobacco smoke or chew for over a month."

"We were just about to prepare some coffee and make a meal."

"Good enough; did you say coffee? Well, I have struck Elysium; I haven't tasted a cup of coffee in a year. You see I was snowbound away up in the mountains; fortunately I had plenty of dried meat, and I was compelled to wait until I was thawed out."

Brooks commenced making the coffee, and while doing so the woodsman asked:

"Are you regular hunters?"

"No."

"Ever in the mountains before?"

"Never."

"You've been taking great chances."

"We have?"

"Yes."

"How so?"

"The mountains are full of bad Indian fugitives, and they are very ugly. Some are parts of a raiding gang of bucks, and others are rascals who have made a kick out at the reservation. I've met twenty of them in the last ten days; they are in squads of twos and threes, and they are full of fight."

"We have met some of them."

"And you managed to escape?"

"We had a fight with one party."

"You did?"

"Yes."

"How did you come out?"

"Ahead, I reckon, or we would not be here."

The conversation was between the woodsman and Desmond.

"What brought you into the mountains—are you tourists?"

"No."

"On business?"

"Yes."

"Surveyors?"

"No."

"I thought not; no use to survey out this way. I suppose you are looking for a lost mine."

"Well, we might take in a lost mine or find a new one, it don't matter."

"Ah! I see; well, so far you've been lucky, but you've been taking desperate chances."

"Oh! that's a way we have."

The coffee was soon prepared and Brooks produced some dried meat and a few crackers, and the three men, so strangely met, sat down to enjoy their meal. The woodsman was offered the first cup of coffee, and as he drank it down, all hot and steaming, he smacked his lips and exclaimed:

"Well, that was good; that cup of coffee makes us friends. I may do you a good turn."

"Good enough; we are ready for a good turn. We've had rather hard luck so far."

"So you are after a mine, eh?"

"Yes."

"You are regular prospectors?"

"Yes."

"You have to strike a surface ledge to make any money. Don't think a claim would amount to much out here unless you found a nest of them so as to attract a crowd, and a town, and a mill, and all that. According to my idea the mines out here all need capital to work 'em in case you should strike one."

Regardless of possibilities, as the night was a little chilly, Brooks had created quite a blaze, and by the light of the fire he had a fair chance to study the woodsman's face, and finally he asked abruptly:

"Stranger, what is your name?"

The woodsman laughed, and said:

"I thought you'd ask that question."

"You did?"

"Yes."

"Why?"

"Well, it's natural that you should, but that ain't the reason I thought so."

"It is not?"

"No."

"Well, why did you think so?"

"I was going to ask your name."

"Certainly; my name is Brooks."

"I thought so."

"You did?"

"Yes."

"What made you think my name was Brooks?"

"Can't you guess?"

"No."

"Why did you ask my name?"

"As you said, it was a natural question."

"That ain't the reason you asked it."

"It is not?"

"No."

"Well, you may tell me the true reason."

"You've been studying my face."

"I have."

"You think you've seen me before somewhere?"

"Well, you did see me before."

"I did?"

"Yes."

"When and where?"

"Just look sharp and see if you can't place me."

"I can't."

"It was a great many years ago."

"It must have been; but to tell the truth, there is something very familiar in your face."

"Yes, and you discovered it at the start, but you don't place me; I placed you. I didn't until you mentioned your name."

"You now recall?"

"I do."

"Where have we met?"

"Try to remember."

"Tell me your name."

"Oh, certainly, by and by; but in the meantime pay me the compliment of remembering who I am."

"You have the advantage."

"How?"

"I told you my name."

"I will tell you mine in good time, but try to remember."

"I give it up."

"You do?"

"I do."

The woodsman laughed, and said:

"We slept together one night."

"We did?"

"Yes."

"When and where?"

"And now you can't recall?"

"I cannot."

"You are a square man, but there has come a change over you."

"Did we meet often?"

"No."

"Were we intimate?"

"Well, yes, for the time being."

"I give it up."

"You don't place me?"

"No."

Again the woodsman laughed and said:

"Do you remember about fifteen years ago a young fellow, tired, wet, and hungry, tried to find shelter in a freight car?"

"Hello! you are not Henry Creedon?"

"Yes, I am, and this is the second time you've fed me. You appear to be my good angel; I may prove your good angel."

"So you are Henry Creedon?"

"I am," and turning to Desmond, Creedon said:

"Your friend there one night made a fight for me, fed me and found shelter for me. He was a tramp then; I was footing it out West here."

"Henry," said Brooks, "what have you been doing all these years?"

"Mine hunting."

"Mine hunting for fifteen years?"

"Yes."

"And have you found a mine yet?"

The woodsman laughed, and Brooks said:

"Desmond, we did indeed take desperate chances, and we've been making a fool's chase, I reckon. Here is a man who has been mine hunting for fifteen years and has not found one yet. Where do we come in?"

"I'll tell you," said Creedon; "it's luck when you find a mine. More are found by chance than are discovered by experts, but I think I've found one; I can't tell. You see, I was raised in a factory town, I've had no education and I can't tell its value. I know where the find is located, however, and some of these days I'll strike a prospecting party who will have an engineer with them, and then I will know the value of my find."

"If you take a party in with you they will demand a share."

"Certainly."

"Do you intend to share with them?"

"I can't do otherwise."

"Yes, that is so; suppose I find an engineer for you?"

"I suppose you will want a rake in."

"Certainly."

"Well, Brooks, I'll tell you, I don't want to start in on a divide with everyone, but I've made up my mind to take you in with me. I know you are a kind-hearted and honest man, even though you are a tramp, a whisky-loving tramp, and that I remember you emptied my canister that night."

"Yes, but I am not drinking now; I've reformed."

"You have?"

"Yes."

"So much the better for you."

"I've something to tell you."

"Go it."

"I am just the man to establish the value of your mine."

"You are?"

"Yes, I am."

"How is that, eh? Have you become an expert after being in the mountains six weeks? and I am not in one way, and I've been here for fifteen years."

"I was an expert before I came to the mountains."

"You were?"

"Yes."

"How is that?"

"I am a civil engineer by profession."

"What's that?"

"I am a civil engineer by profession."

"You don't tell me!"

"That's what I tell you, and I tell you the truth."

"Then you are just the man I want."

"I said I was; I am more than an engineer, I am a mineralogist and a geologist."

"Hold on, don't overcome a fellow out here in the mountains; if you are a civil engineer that is enough for me. Hang your mineralogy and geology; what I want is a man who can estimate. No doubt about the ledge I've struck; the question is, how much will it cost to mine it; how much is there of it? You see I've had some experience here in the mountains, and sometimes we strike what is called a pocket; we might find gold for a few feet one way and another, and then strike dead rock and no gold. I ain't a mineralogist or geologist or a civil engineer, and I am afraid my find won't amount to much, but it is worth investigation, and as you are able to estimate we will make a start. To-morrow I will take you to my ledge and then we will know whether we are millionaires or tramps—eh? mountain tramps—but I am grateful for this food and coffee, and now if you'll give me a little tobacco I'll be the most contented man in the mountains, whether my mine turns out a hit or a misthrow."

So tobacco was produced; Brooks himself was an inveterate smoker, and since being in the mountains Desmond had taken to the weed, and there was promise that some day he might become an inveterate.

The three men had a jolly time, but in a quiet way. Creedon was a good story teller; he had had many weird experiences in the mountains. He had acted as guide to a great many parties, he had engaged in about fifty fights with Indians during his residence in the great West, and had met a great many very notable characters.

When the men concluded to lie down to sleep for the night they extinguished their fire, and each man found a crevice into which he crept, and only those who have slept in the open air in a pure climate can tell of the exhilarating effects that follow a slumber under the conditions described.

Desmond was the first to awake, and he peeped forth from his crevice and glanced down toward the point where the fire had been, when he beheld a sight that caused his blood to run cold. Five fierce-looking savages were grouped around the spot where the campfire had been, and he had a chance to study a scene he had never before witnessed. He beheld five savages in full war paint; they were dressed in a most grotesque manner, part of their attire being fragments of United States uniforms, showing that the red men had been in a skirmish, and possibly had come out victorious, and had had an opportunity to strip the bodies of the dead.

A great deal has been written about the shrewdness of redmen. They are shrewd when their qualities are once fully aroused and they are on the scent, but they are given to assumptions, the same as white men. Of course Creedon was practically to be credited when he said that the Indians assumed there had been a camp there and that the campers had departed, but had they made as close observations as when on a trail they would have made discoveries that would have suggested the near presence of the late campers.

Creedon had as far as possible destroyed all signs when raking out the fire of a recent encampment, but an experienced and alert eye can detect the truth despite these little tricks.

Desmond saw the Indians: they were a hard-looking lot, the worst specimens he had ever beheld, and they were assassins at sight, as he determined. He was secure from observation, but it was necessary to warn his comrades, who were in different crevices, and at that moment Creedon actually snored. He was in the crevice adjoining the one where Desmond had taken refuge.

The Indians were too far away to overhear the snore, but it was possible the man might awake and step forth; then, as Desmond feared, the fight would commence. He did not desire a fight; he might think the chances would be with his party, as only two of the Indians had rifles, but then if even one of their own party were kicked over it would be a sad disaster.

The lad meditated some little time and studied the conditions. He crawled into his crevice, and, lo, he saw a lateral breakaway. He might gain Creedon's berth, as he called it, without chancing an outside steal. Fortune favored him; Creedon's crevice was one of several rents in the rock, and he managed to reach the sleeper's foot, and he cautiously touched it, fearing at the moment that Creedon in his surprise might make an outcry or an inquiry in a loud tone, but here he learned a lesson in woodcraft. Creedon did not make an outcry; he awoke and cautiously investigated, and soon discovered that Desmond had touched him and was seeking to communicate with him. He demanded in a whisper:

"What is it, lad?"

"There are Indians in the gulch."

"Aha! where?"

"Down where we were camped last night."

"You keep low and I will take a peep."

Desmond could afford to let Creedon take a peep. The woodsman did peep and took in the situation, and he said:

"You are smaller than I am; does the rent where you are run to the berth where Brooks is sleeping?"

"It may; I will find out and go slow; we don't want a fight if we can help it, but we've got the dead bulge on those redskins if we have to fight."

Desmond crawled forward beyond the rent where Creedon had lodged, and he found the space much wider as he progressed, and soon gained the opening where the rent terminated in which Brooks had lain all night. Desmond glanced in, and, lo, Brooks was inside awake, and had already discovered the presence of the Indians, and so far they were all right.

"Have you been able to notify Creedon?" asked Brooks.

"Yes."

"What does he say?"

"He bade me arouse you."

"I discovered the rascals as soon as I awoke."

"All right; lay low and I will learn what Creedon advises."

Desmond crawled back and said:

"Brooks is awake and wants to know what we shall do."

"There is only one thing to do: we will lay low, and if the rascals do not discover us all right; if they do discover us it will be bad for them and all right with us again, that's all. And now you and Brooks just keep out of sight and let me run the show."

Word was passed to Brooks, and Desmond with the tramp lay low. As it proved there was not much of a show to run, as the Indians moved away after a little, but Creedon did not permit his friends to go forth. He said:

"You can never tell about these redskins; they might suspect we are around, and their going away may be a little trick; they are up to these tricks."

Hours passed, and Creedon still kept his friends in hiding, and it was near evening when he stole forth, saying he would take an observation. After a little he returned and said:

"It's all right; come out."

Creedon said he had discovered evidence that the redskins had really gone away.

"Why couldn't you have found that out sooner?"

The woodsman laughed and said:

"They might have found me out then; as it was, according to the tales you and Brooks tell, I took a desperate chance."

"Shall we get to work and have a meal?"

"Not much, young man, you will have to control your appetite for awhile. Remember, I am captain of this squadron. I'll lead you to a place, however, where we can build a fire and camp and eat without fear. I am posted around here; I know the safe places."

The party started on the march, and Desmond felt quite irritated; he had gone nearly twenty-four hours without eating, and he said:

"I am ready to even fight for a meal."

Creedon laughed and said in reply:

"You may have a stomach full of fighting yet before we find the mine."

"I thought you had located it?"

"Yes, but it's a week's tramp from where we are at present, and we may have some lively times before we arrive at the place."

It was nine o'clock at night when the party arrived at one of the most peculiar natural retreats Desmond had ever seen. It was a cave, as we will call it, in the side wall of a cliff rising from a gulch even more wild and rugged than the one where the party had camped the previous night. Some mighty convulsion of the mountain had separated the whole front of the cliff from the main rock, so that a space of at least twenty feet intervened, and between yawned a dark abyss that led down to where no man had yet penetrated. Creedon led the way up along a ledge of ascent which lined the outer edge of the great mass of detached cliff. Once at the top he descended on the inner side. It was night, but he had taken advantage of a mask lantern which he carried with him, and which he said was the most useful article in his possession. He added:

"These lanterns may belong to the profession of detectives and burglars, but I've found them the most useful articles a cliff-climber can own. They are different from other lamps and torches; you can control the one ray of light and indicate your path without any trouble whatever."

This was true, as the guide demonstrated, and his party walked along the narrow ledge without any fear of being precipitated over; all it required was a good eye and a steady nerve, and they possessed these necessary qualifications.

The guide at length came to a halt, and said:

"You stand here and I'll get my bridge."

He proceeded along alone, but soon returned with two saplings, which he had strung together, and of which he had made a rope ladder.

Desmond was greatly interested, and watched the guide as he threw his ladder across the intervening abyss, and then he said:

"It will take a little nerve to crawl over, but once over we are all safe, and I've got a storehouse over there. I prepared this place with a great deal of patience and labor. We can spend two or three days here. I know you will enjoy it, and we can take a good long rest. I will go over first and then hold the light so you two can follow."

Desmond glanced at Brooks, and asked:

"Will you risk it?"

"Yes, I will, lad; I am not the fellow I was about six months ago; I can climb a steeple now."

The guide went over, creeping across. The saplings bent under his weight and made a downward curve, so that when he attempted so ascend on the opposite side it was a climb up, but with the ropes made of woven prairie grass and sticks and boughs he easily ascended. He had carried his lantern with him, and he flashed its light across his bridge and asked, "Who will come next?"

"You go," said Desmond to Brooks.

The tramp did not hesitate, but started to crawl over the oddly constructed bridge, and he did so as well as the guide had done. Then Desmond crossed and the instant all hands were over the guide took up his bridge stowed it away, and said:

"When we cross back it will be in the daytime, and much harder."

"Much harder in the daytime?"

"Yes."

"I should think it would be easier."

The guide laughed and said:

"It might appear so, but in the daytime you will realize just what you are doing. You will see the dark abyss beneath you, and when the bridge sways downward your heart will be in your throat, I tell you. At night, however, you do not know just what you are doing."

Desmond saw the truth of what the guide said, and observed that the man was quite a philosopher.

"Now let me go in advance," said Creedon.

He led the way and soon turned into what he called Creedon Street. It was a broad opening with a solid flooring, and walls of rock on either side—the most singular and remarkable rock conformation that either Brooks or Desmond had ever seen. The guide walked right ahead boldly; he evidently knew that there were no rents down which they might plunge.

"Here is Creedon Hall," said the guide, as he turned into a broad opening and flashed his light around. The party were in a cave, and yet we can hardly call it a cave; it appeared to be merely a huge underline in the side of the cliff, as it was open, as the guide said, facing Creedon Street.

"I will soon have Creedon Hall illuminated for you," said the guide. He secured some wood, and as Desmond followed him he saw that he had abundance of it, and the guide said:

"This wood, some of it, has been stowed here for over ten years, and we can have a jolly fire in a few minutes, and no fear of attracting Indians or any one else. We are as safe here as though we were making a grate fire in a big hotel in New York."

Creedon made good his word, and soon Creedon Hall was brilliantly illuminated, and Desmond was delighted. He exclaimed in his enthusiasm.

"This is just immense!"

"Well, it is."

Brooks also was delighted; he set to work to make the coffee and prepare the meal, and Creedon lay down on his blanket and lit his pipe, while Desmond wandered around the cave, as he persisted in calling it. He discovered several outlets from Creedon Hall, and he made up his mind that as soon as his friends were asleep he would steal the mask lantern and go on an exploring expedition. It was a jolly party that sat down to coffee, cold dried meat, and crackers. Brooks had been very sparing of his crackers, and had at least five pounds of them at the time he and Desmond met the guide.

"When did you discover this place?" asked Desmond.

"I did not discover the place; it was revealed to me by an old hunter, a Mexican, and how he discovered it he would never tell. The old man had a great many secrets, and I have sometimes thought that there was gold hidden here somewhere. I've spent days searching for it, but never could find anything of the value of a red cent."

"Where is the old Mexican now?"

"That's hard to tell, lad; he died about five years ago, and his body was carried to the ruins of an old Spanish church and there buried as he had requested long before he died. He was a strange old man; he possessed many secrets, but they died with him. It is possible he meant to reveal them some day, but death caught him and he went out with his mouth closed as far as his secrets were concerned. He was a sort of miser in secrets. I did think that some day the old man would reveal something of value to me; he pretended to think a great deal of me. I saved his life at a critical moment; he was actually bound to the stake, and I shot the rascal who was about to light the fire. They intended to burn him alive, and the arrival of myself and party was just in time."

"Do the Indians still burn their prisoners at the stake?"

"These were not Indians—they were his own countrymen. They had tried to force a confession from him, and because he refused to reveal the whereabouts of the gold they thought he had stored away somewhere, they were set to murder him in anger and revenge."

"And you saved him?"

"I did."

"And he never revealed his secrets to you?"

"Only the secret of this cave. He often made strange remarks and hinted that some day I would receive my reward. We roomed here together all of one winter, but he died and never opened his mouth to reveal where his gold was, if it is true that he had any. I believe he did, but it will never do me any good, and I do want to make a fortune somehow, but I suppose I never will. Yes, lad, there are thousands of skeletons of gold-seekers hid away in caverns in these mountains, victims of the same ambition which is leading us to take such desperate chances."

Desmond was very greatly interested in the story of the old Mexican, and he asked a number of questions.

"You never got the least inkling as to where his gold was hidden?"

"I don't know that he had any gold; it is only a suspicion on my part."

"He lived in this cave?"

"Yes."

"Did you ever search here?"

"Well, you bet I did."

"And did you explore?"

"You bet I did."

"And you never found anything?"

"I never did."

"Nor secured any indication?"

"Never."

"Possibly you did not look in the right place."

"That is dead certain," came the natural answer.

It was about midnight when the older men lay down on their blankets to sleep. Creedon had a big silver bull's-eye watch, and he said he always kept it going.

Desmond pretended to lie down and go to sleep also, but his head was filled with visions of the Mexican's hidden gold. He had an idea that Creedon's investigations might have been very superficial; he determined to make a thorough and systematic search, and he actually believed he would find the hidden gold.

Brooks and Creedon were good sleepers; both were very weary and they were soon in a sound slumber, and then Desmond arose, stole on tiptoe over beside Creedon and secured the mask lantern. A strange, weird scene was certainly presented. There had been a big fire; the embers were all aglow and illuminated the cave. There lay Brooks and Creedon, looking picturesque in their hunting garb, and there was Desmond stealing on tiptoe under the glare of the firelight to secure the mask lantern.

Having secured the lantern the lad moved away and made for a crevice which promised the best results. He knew enough of rock conformations to go forward very carefully, always flashing his light ahead and studying the path in advance, and so slowly, carefully, and surely he moved along until he had traversed, as he calculated, a distance of two hundred and fifty feet, when suddenly his flashlight revealed a solid wall in front of him.

"Here we are," he muttered, "and no mistake."

Desmond saw that his explorations in that direction had ended. He retraced his steps and selected a second crevice along which he made his way, and at length he landed in a pretty good sized inner cave.

"Well, I reckon we've got it here."

The lad proceeded to search around with the care of a detective looking for clues. He did find evidences of some one having been in the cave; he found the handle of a dirk, a small bit of a deerskin hunting jacket, and finally a little bit of pure gold. He examined the latter under his lamp, satisfied himself that it was a nugget of real gold in its natural state, and his heart beat fast.

"I've got it at last," he muttered; "yes, I thought I knew how to carry on this search. Creedon must have done it too hurriedly."

Desmond felt quite proud of his success; he had struck it sure, as he believed, and he continued his search, and was intently engaged when suddenly he heard a sepulchral groan at the instant he had plunged into a sort of pocket and was feeling around; but when he heard that groan he started back into the cave and stood as white as a sheet gazing around in every direction, and there was a wild terror in his eyes. He stood for fully two minutes gazing and listening, and finally he said:

"Great Scott! what was that I heard—a groan?"

Desmond, although brave and vigorous, after all was but a lad of less than eighteen. He could have faced a grizzly bear, but when it came to the supernatural he was not equal to it. The fact was he was dead scared, and, then again he believed he had really struck the hidden recess where the old Mexican's gold was secreted.

The young are more susceptible to superstitious fears, as a rule, than older people; they are not skeptical.

Desmond listened a long time, and as he did not hear the noise again, and feeling an intense desire to find the hidden treasure, he again went to the rock pocket and plunged in, but immediately there came again the groan, clear, distinct, and unmistakable, and also a voice commanding:

"Go away, go away; do not disturb my gold."

The lad leaped out into the main cave again, and he trembled from head to foot. He had never received such a shock in all his life; he had never really believed in ghosts—never thought much about them indeed—but here he had at least evidence that the dead did watch their treasures. Still, the desire to secure the wealth was strong upon him; naturally he was, as our readers know, very nervy, and he determined to argue with the ghost. He reasoned that the hidden wealth could be of no benefit to the spirit where he was, and he thought he might talk him into keeping quiet.

It was in a trembling voice that Desmond asked:

"Is the spirit here?"

The answer came:

"I am here."

A more experienced person than Desmond would have gotten on to the fact that it was very strange that the spirit should answer him in such good English, it being supposed to be the spirit of a Mexican, but spirits probably can talk any language. At any rate, Desmond did not stop to consider.

"Do you own the gold?"

"Yes."

"Why can't I have it? I've found it."

"You get away as quick as you can or I'll seize you."

Well, well, this was a great state of affairs; Desmond did not ask any more questions. He seized his lamp and started to limp from the cave, and he was white and trembling. He made his way to Creedon Hall and beheld Brooks and Creedon standing over the fire. On the face of Brooks there was an amused look, and on Creedon's an expression of real jollity.

"Great sakes! Desmond," demanded Brooks, "where have you been? I awoke and found you missing, and Creedon and I have been scared almost to death."

Desmond tried to assume an indifferent air, and said:

"I wasn't sleepy, so I thought I would go and explore a little."

"You had better be careful how you explore around here."

"Why?"

"Well, that's all; I won't say any more, but be careful, or you may be suddenly missing."

"What did you find, boy?"

"I'll tell you all about it in the morning."

The men retired to their blankets and Desmond also lay down, after having promised that he would not attempt to explore any more that night.

He did not sleep, however; the phantom voice, the treasure, and his discovery kept him awake, and he lay thinking about ghosts and goblins, and he muttered;

"Hang it! I never believed in ghosts;" then as he lay there, there came to his mind a recollection of the jolly look that had rested on the face of the guide, and there came to his mind a suspicion, and then a certainty, that he had been fooled. He was a wonderfully sharp lad, and he began to think the whole matter over, and he recalled the fact that the ghost had spoken good English.

"Hang me!" he muttered, "if I don't believe I've been made a victim of a huge joke, and Brooks and Creedon are both guilty in aiding to give me a scare. All right, to-morrow we will see all about it; I'll get square."

Desmond did fall asleep at length, and when he awoke Brooks and Creedon were eating their breakfast, and Creedon said as Desmond joined them:

"So you were exploring last night?"

"Yes."

"What did you find?"

"Gold."

"You did?"

"Yes."

"Oh, come off."

"I did."

"You think you did."

"I did, I'll swear I did."

"Where did you find it?"

"In a cave which one of those passages leads to."

"You found gold?"

"Yes."

"You will have to be careful."

"Careful?"

"Yes."

"Why?"

"You'll strike the ghost."

"The ghost?"

"Yes."

"What ghost?"

"The ghost of the old Mexican."

"I did think I heard a groan. Tell me about the old Mexican."

"I've told you all I know about him, and I'll tell you that in my opinion it will be dangerous to meddle with his gold, even if you found it."

"Could that old Mexican speak English?"

"A little."

"Only a little?" repeated Desmond.

"Yes."

"Then it's just as I suspected; I tell you I was scared at first, but when the old ghost answered me—"

"When the ghost answered you?" demanded Creedon.

"Yes."

"Did you see the ghost?"

"I heard him—that is, I thought I did—and I spoke to him, but he gave me back such good English I made up my mind that you didn't know how to play a joke. Next time stick to the broken English; you might have scared the life out of me then."

Brooks and Creedon laughed, and the latter said:

"Well, you are smart, you are; but, lad, let me tell you something: don't spend time looking for the Mexican's gold."

"Why not?"

"I've explored every nook and cranny in this mountain, and there is no treasure hidden here."

"But I found some gold."

"You did?"

"Yes."

Creedon and Brooks stared.

"Are you in earnest?"

"I am."

"Where did you find it?"

"Well, I am going to consider awhile before I tell."

Brooks looked Desmond straight in the face, and asked:

"Boy, honest, did you really find gold?"

"Yes, I did."

The matter began to assume a very serious aspect, for Desmond spoke seriously.

"If you found any gold, lad, you've beat me."

"I did find gold."

"On your honor?"

"Yes."

"Well, here we are on shares; tell us all about it."

Desmond laughed in turn; they had had their laugh and he had his laugh, as he said:

"Here is what I found."

The lad produced the little nugget he had picked up and then Creedon laughed, and said:

"By George! that is the bit of gold I lost, and I had a good hunt for it."

Our hero had been impressed by Creedon's statement that he had examined every nook and corner in the mountain, and yet he did feel a sort of hankering notion that he could find the gold, and he said:

"I want to explore again."

"All right; it can do no harm, but I will relinquish all claim now to any gold that you may find in this cave."

"I'll take you at your word," said Desmond.

Of course the youth had no real hope of ever finding any gold, but it is a known fact that such finds have been made, and sometimes the skeletons of the owners have been found bleaching beside their gold.

Desmond was somewhat impressed by the words of Creedon, but still insisted that he would like to conduct an exploration.

"You will only go over the ground that I have already gone over."

"I know that, but I propose to look around all the same."

Desmond had been doing considerable thinking. He questioned Creedon again and again, and made out that the old Mexican had lived in the cave along with Creedon for months at a time, and as he learned, the old man had thrown out a great many hints. These hints meant something; and then again, if he had hidden his wealth in the cave he had done it so securely and well that he had no idea of its ever being discovered until such time as he saw fit to disclose the fact. Desmond knew how there were some strange conformations in the rocks; the very place they were in was a testimony to the strange freaks that nature in its upheavals can and does create.

Brooks had nothing to say about the matter, and Creedon did remark finally:

"Of course, as I've said, it can do no harm, but be careful you don't strike—"

Desmond here interrupted, and said:

"I ain't afraid of ghosts; I've met one and I've got used to them."

"I don't mean a ghost, I mean a crevice; go very slow and carefully, or you may become a ghost yourself."

Right here we wish to exchange a few words with our readers in regard to these rock conformations. Right in the State of New York, in Ulster County, and in what is called the Shawangunk Mountains, there are some of the most wonderful caves and crevices, and in some of these caves during the winter the snow drifts down, and in the spring becomes a solid mass of ice, and the writer remembers upon one occasion after a long and weary scramble over rocks under the face of a cliff which towers up and overlooks counties, being shown a rock cave where there was a solid mass of ice, which, in its contour resembled a ship. The ice must have been at least sixty feet in length, twenty feet broad, and fully forty feet high, and adjoining it were all manner of caves. These caves are within a few miles of several settlements, and possibly at the time of the visit of the writer had not been entered by over a dozen persons. In these mountains are some very remarkable rock conformations, and we merely mention this fact to the lads in the East, who may think that these stories of rock caverns are exaggerated. There are probably hundreds of caves in the Catskill and Shawangunk Mountains that have never been entered or explored since the days when the early settlers may have found them while bear hunting.

Desmond had been raised, as we have stated, near the mountains, and probably had explored many rock caverns, and it is because of this fact probably that he was not surprised when led to the cave where he first beheld the girl Amy Brooks. That cave still exists and is well known to many of the people living in its vicinity, and in our description we adhered to almost absolute accuracy.

Creedon was a rough and ready sort of man, but not, the fellow, as Desmond argued, who would apply himself to a critical study. It was a great thing to have learned the facts concerning the old Mexican, and the lad really believed that there was gold secreted somewhere in one of the little cavities in that perforated mountain.

Creedon started in to relate to Brooks the facts about the mine he believed he had discovered, and Desmond, taking the mask lantern, started off to explore.

"You will burn out all my oil, lad; that is the only harm you will do, and certainly little good. I cannot replenish the oil when it's burned out, and I've been very careful, holding it for only such occasions as when we came here across the chasm."

Creedon explained that he had only carried with him one can of oil, which had lasted him to date.

Desmond started off and went direct to the crevice he had first entered, and Creedon smiled as he saw him go in there, remarking to Brooks:

"The lad will run up against a stone wall sure, but he is enthusiastic; it will be a lesson to him."

"Can't tell about that lad," said Brooks, "there is method in his enthusiasm."

"That's all right, but I was camped in here one whole winter, and as I told you, there is not a nook or cranny that I have not explored."

"But there are others," said Brooks, with an odd smile on his face.

Meantime, Desmond followed the crevice until he came to the stone wall. He knew about the same wall, but he was working on a certain theory. He was like the Captain Kidd treasure-seekers—the discouragement of others did not in any way discourage him, and we will here say that a similar persistence in any walk of life, as a rule, leads to great results.

Desmond, as stated, arrived opposite the stone wall, and he commenced a calm, steady, determined examination. First appearances would have discouraged any man, being faced as he was by a solid, smooth face of rock. He stood contemplating the mass before him, and then with the ray of light from his lantern he ran all over the rock.

"By ginger!" he muttered at last, "I reckon it's true. There does not appear a hole big enough in that rock for a spider to crawl through; but, hang me! I've got an impression."

There appeared to be a break in the rock just where it joined with the roof of the cave. Desmond rolled a bowlder over against the rock and mounted, and ran his finger over the crack. It was not a large crack and offered no encouragement, but the lad was determined not to be satisfied until he had established facts beyond all dispute. He ran his finger, as stated, along the crack, and his knuckle pressed against the roof, and to his surprise there appeared to be a loosening. He examined it and he saw that there was a uniform crack running along the roof inclosing a space about two feet square. The lad instinctively pressed on the center between the cracks, and lo, there appeared to be a piece of the roof that yielded. He pressed harder and satisfied himself that the piece of rock between the cracks in the roof was movable. The discovery caused his heart to stand still, and he muttered:

"Great Scott! but I've found it." He flashed the light on the crack and thought he could discern where there had been some chiseling. He made every effort to shift the rock out of its place, but it was too much for him, owing to the fact that he could just about reach it. He did not have purchase enough to exert his full strength.

He stepped down on the floor again and commenced to consider, and then he determined to return to the main cave and solicit Brooks and Creedon to go to his aid.

When he re-entered the main cavern Creedon with a laugh said:

"Well, lad, did you run up against a stone wall?"

"I did."

"I told you it was of no use to search these crevices. I've explored every inch."

"You have?"

"Yes."

"I think not."

Brooks knew Desmond so well he discerned that the lad had really made a discovery, but he said nothing.

"You think not, eh?"

"I do."

"That would hint that you had found something."

"I have."

"What have you found?"

"I don't know yet, but I am certain I have found a cranny or nook that you never explored."

"You have?"

"I have."

"What have you found?"

"Oh, it may be that it's 'tellings,' as the boys say."

Creedon looked at the lad in a curious way.

"It cannot be possible," he said, "that you have found anything?"

"Yes, I have."

"What have you found?"

"Guess."

"It's no time to guess; what have you found?"

"I'll show you what I've found; I want your help."

The lad found a piece of sapling about seven feet in length, and said:

"You gentlemen come with me; I'll show you something."

Animated by great interest and curiosity, Brooks and Creedon followed Desmond. He led them to the little rock cave where the crevice abutted on the solid wall of rock, and he said:

"Now what do you see?"

"We see the rock."

"Is that all?"

"Yes."

"Look sharp; there is something you have not discovered before."

"What is it?"

"Look."

"I've looked."

"I reckon when you did look upon the occasion of your former visits you did as you are doing now—only looked, but you did not search."

"Have you searched?"

"Yes, I have."

"And you've found something?"

"Yes, I have."

"What?"

"Oh, look."

"I'm done looking."

"Then let me show you."

Desmond took the strong piece of sapling he had brought with him and jammed one end with great force against the square piece of roofing, and the piece of rock moved.

Creedon gazed aghast and exclaimed:

"By all that's strange and wonderful, but I believe you have unfolded the Mexican's secret."

"I think so; and now lend me your strength, both of you, and let's see if we can move that loose piece of rock. I'll bet there is an opening there."

"You are right—yes, lad, you have indeed raked into the old Mexican's treasure den; I can recall now some words he once spoke."

"Don't spend any more time recalling; let's shove that rock aside if we can."

The two men lent their aid to Desmond, and sure enough they did raise the piece of rock, and by hoisting it they managed to move it aside a trifle, enough to reveal the fact that there was a chamber above, and that the opening was through the piece of rock.

It was a reward of Desmond's persistence, but after all it was accident that had revealed to him the opening.

By hard work the men finally succeeded in moving the rock aside, and there was disclosed the opening, and Desmond said:

"Now let me stand on our shoulders with the light and I will tell you what it is we have found. There is something there to reveal, I am dead sure."

The two men assisted Desmond to their shoulders. He took the lantern and shoved his head through the opening, and then flashed the light around, and with a joyful shout exclaimed:

"We've got it!"

"This beats me dead," said Creedon.

Both men were greatly excited, for it did appear that they had made a great find of hidden treasure.

Meantime, Desmond managed to force himself up and disappeared in the cave. He glanced around and beheld a sight that filled him with varying emotions.

The chamber was not more than four feet square, but on the floor in one corner was a shining heap. It shone under the ray of his lantern as he flashed the light upon it. He took a handful of the shining stuff and passed it down to Creedon, handing him the lantern at the same time, and he said:

"You are a good judge; tell me what that is?"

"It's gold dust," cried Creedon; "how much is there of it?"

"Oh, barrels full, I should say."

"Great ginger! lad, you've struck it."

"Well, it won't run away, I reckon, but give me your hat and I'll fill it."

"Is that to be my share?"

"No, we're only giving you the first whack at it, that's all."

Desmond filled Creedon's hat with the dust and then descended, and the whole party made their way to the outer cavern.

Once in the outer cavern, Desmond said:

"It's now a matter of business."

"Well?"

"How shall we divide?"

"You are the finder," replied Creedon; "you are to decide."

"You leave it to me?"

"Yes."

"I'll make it an even divide all round."

"Boy, it's a great discovery."

"What do you think of its value?"

"It depends upon the weight, but from your description I should say we had a ten-thousand-dollar find."

Desmond's eyes opened wide, and after a moment he asked:

"Does it really belong to us?"

"It does certainly; I am really the appointed heir of the old Mexican, but anyway treasure-trove goes to the finder who can establish a right to it."

"We can," said Brooks.

"You bet we can, and it is ours, but it's strange how the old Mexican's secret has been opened up. Here I've had five years to search for this gold and failed to find it, and this lad gets on to it in one day."

"It was a mere chance."

"Well, yes, to a certain extent; but if you had not been so persistent you would not have developed the chance and made the find possible."

"How did the old man accumulate this gold?"

"It's plain enough; he has known some stream and has washed it, and possibly it took him ten years to gather the heap you found there; but how well he did it!"

"He did, sure."

"How shall we make a divide?"

"Easy enough if you will let me make a suggestion."

"Certainly."

"We will carry it all out here; we run no risk, no one will ever penetrate to this retreat; then when we have it all carted out here we will divide it, a coffee cup full at time."

"Good enough; that suits me."

"But wait; I've a better proposition if you will accept it."

"Go ahead."

"Let's leave it where it is, go on to my mine, and if it amounts to anything we will have the capital to work it ourselves."

Desmond glanced at Brooks, and the man said:

"That is a good proposition."

Brooks was less suspicious than Desmond, but the lad determined to accede to the proposition, and it was decided that on the following morning they would start for Creedon's mine, and the guide said:

"We will start before daylight."

"Why?"

"We had better cross the chasm in the dark; I am afraid you would hardly recross it if you were to behold once what would be underneath you."

It was so decided.

The party made all their preparations and on the following morning, before daylight, with the aid of Creedon's ladder the party crossed the chasm and proceeded on their way toward the place where Creedon's mine was located. They managed to secure enough game which they cooked and had for food, and commenced their long march, and it was a long march. They had been five days on the tramp, and stopped one night to camp, when Creedon said:

"In the morning we will be on the ground."

The place where they were camped was a mountain glen, and our young friend Desmond, being in splendid health, was exceedingly happy. The life thus far had been one of constant excitement, and therefore at his age one of continuous enjoyment, and besides, to crown all, he was comparatively rich. As intimated, Creedon had valued the dust at ten thousand dollars, and when it should be turned into money Desmond could indeed clear his mother's farm and go to school, and then to college, and it was his highest ambition to obtain a fine education. He was an ambitious lad.

Creedon was restless and excited all the evening; for him a great decision was to be rendered. He had come to know that Brooks was indeed an expert, and should the latter decide that his claim was of value it meant that for which he had been struggling a long time, as he had said, for fifteen years.

Creedon did not sleep; much danger would not have kept him awake, but the possibilities of the dawning day did cause exceeding restlessness. Desmond noticed that the woodsman did not sleep and went over and sat near him.

"What's the matter, lad; why don't you sleep?"

"Why don't you sleep?"

"To tell the truth, I can't."

"Neither can I."

"I don't see what keeps you awake."

"The possibilities of the coming day."

Creedon was in a thoughtful mood, and Desmond asked:

"Why are you so anxious to get rich?"

"Lad, I'll tell you: I am thirty-three years old; I started from home when I was less than eighteen; my father was a poor man. Living in our town was a rich man who had a lovely daughter; she was just fifteen. I had known her from the time we were wee little tots, and we fell in love with each other, although she was fifteen and I but a little past seventeen, but her father was rich; he despised low people, and that girl and I agreed that I was to leave home, go into the world and earn a fortune, and go back and claim her. We made a solemn agreement, pledged ourselves under the stars, she was to wait for me even if I did not return until I was a gray-haired man. Boy, she is waiting yet; she is a handsome woman now—I have her photograph—and once a year I receive a letter from her. She has urged me to return; her father is dead and she has a competency in her own right, but I am not willing to go home, marry her and live on her money; and besides, I want to get rich—real rich. I wish to buy her the finest house in our native town, give her horses and carriages; I'll die before I will return poor. The people in the town have often and often hurt her feelings by their deridings, telling her that I had forgotten her, that if I did succeed in winning a fortune I would never return to her, but would marry some one else. They told her I was a thriftless vagrant, never would get rich, and through all this she has remained true to me, and every time I receive a letter from her she urges me to return. I don't know; if my mine turns out all right I will return, if it don't I will not return, and here I am just about to learn what the chances are. It means to me life, love, and happiness, or a return to the endless longing that has inspired me for the last fifteen years; but, boy, I will never return unless I have a fortune."

"No wonder you are restless, and I am now as much interested in our success on your account as I am on my own."

"I have high hopes, lad—yes, high hopes."

On the morning following the dialogue related, all hands were up bright and early and they started for the mine, and in two hours were on the ground. Creedon was pale as a pictured ghost while pointing out to Brooks the indications, and Brooks also was excited as he made his study.

We will not bore our readers with an account of the investigations made by Brooks, but will state that at the end of the second day he was compelled to announce that the mine was valueless.

Desmond thought he had never seen a more disconsolate look on any man's face than the one that settled over the face of Creedon when the announcement was made.

"Your mine don't amount to anything in itself," said Brooks, "but it carries a suggestion; it is a compass that points to where a valuable mine may be found. We are not in it yet; to-morrow I will make a survey and I may get indications that will carry us to the ledge where the gold ores extend in paying quantities—yes, I think I can read the indications as plainly as though the road were mapped out."

Brooks spent two days, and then said:

"It's all right; there is a mine somewhere, but I must have the proper instruments and testing utensils. I will leave you and Desmond here in the mountains and proceed to the nearest settlement and secure what I need. Creedon, I can almost promise you that we will find a rich digging, and it will be more accessible than this one."

"I have a better plan," said Creedon.

"What is your plan?"

"We will go and get the dust that the lad found; we will carry that to the town, dispose of it, get our money, make our deposits in the bank, and then start in on the search. Possessing the knowledge that you do, we will find a mine. I am not discouraged yet."

It was so agreed, and the party made their way back to where they had their store of dust. Creedon had made some deerskin bags so that the burden would not fall upon one person. The dust was all secured and they made a start for the town.

On the night when they made their last halt before ending their trip in the town, Brooks, the wizard tramp, took advantage of an opportunity to talk to Desmond alone. He said:

"Lad, to-morrow we will be in the town and we will have money. I have a proposition. It will take a year or two to develop matters in case I do locate the mine; you cannot afford at your time of life to spend a year. I do not need you with me now. I am a man again, thanks to you, and I will make a confidant of Creedon. He is a manly, honest fellow, and will watch over me. Our joint interest will make him a splendid sentinel. I feel that we are sure to win, if not in one direction in another. With my scientific knowledge and his practical knowledge we will win, but it may be two or three years. This is a fascinating life for you, but you cannot afford to lose this valuable time."

"What is it you are about to propose?"

"I can send you home with five thousand dollars and I will still have money enough to carry on our purpose. You can clear off the farm and go to school; you are ambitious, and in less than a year you will be prepared to stand an examination for college, and you can go with a cheerful heart, for if my life is spared I will win a fortune for you. I have no use for a fortune myself; I am working for you and Amy."

"But suppose something should happen to you? Do you remember you have not made your revelation?"

"I propose to provide for that; I will confide to you a document. It is not to be opened until you are assured of my death, so living or dead you shall in good time learn the great secret that I have held all these years."

"I must think this matter over," said Desmond.

"There must be no thinking. I have decided as to what you must do."

"And you do not want me to go back at all?"

"No, I want you to go home to the State of New York; I want you to go to clear off the farm and go to school, and I will attend to your affairs out here."

"I will decide in the morning."

That night Desmond thought over the whole matter. He had become fascinated with the life in the mountains, but when he revolved the whole matter in his mind he saw that it was indeed wiser for him to return to his home; and under what joyful circumstances he would return! He could clear the farm and have money in the bank; he could go to school and go to college, and devote his whole attention to study without any worry or fear, and in the morning he greeted Brooks with the announcement:

"I have decided to obey you."

There came a sad look to the face of Brooks, and he said:

"I shall miss you, Desmond, but I feel it is for the best. You are a youth of great promise. I do not mean to flatter you, I am speaking the truth, and it is in your interest that I so warmly advocate your return to the East. I desire that you become an educated man, a graduate of college; I wish you to secure your degree. And let me tell you now there was fate in our meeting, and very remarkable consequences may follow our acquaintance begun and maintained under such strange circumstances."

Desmond had never beheld his strange friend, the wizard tramp, under a similar mood. There appeared to be a prophetic spell prompting the words of the strange man.

"I hope you do not wish to get rid of me."

"No, I am speaking in your interest alone, lad; my life has been a wasted one, yours is just commencing. You can be of some use in the world, I have been a nuisance. I have a strange tale to tell—yes, Desmond, like many others I have encountered a romance in life. I deliberately threw myself away, but where I failed you can win; there is a chance for you to become a useful man; great honor may await you because you possess the qualities that win success. You are brave, firm, and persistent, also enterprising; with these qualities, in this land, any young man can win a success against the great throng of unambitious and careless men like myself."

"Can you trust yourself?"

"I can."

"You are certain?"

"I am."

"You do not need me?"

"I do not."

"Remember, your weakness upon several occasions permitted you to fall."

"I have considered everything; I have an object in life now and a prospect."

"A prospect?"

"Yes."

"Is there anything you are concealing from me?"

"I am considering your interests alone," was the reply.

"But your revelation?"

"It is not necessary for me to tell you once again that I have provided for you to learn the secret of my life in case anything should happen to me."

Desmond at once began his arrangements for a return to the East. He had been away for many months; he had plenty of money; his return would be in great triumph in every way. He purchased fine clothes, which he was able to do even in the far Western town where he was stopping, and when he arrayed himself in his good clothes even Brooks was surprised at the wonderful transformation well-fitting attire made in the youth. Desmond was indeed a fine-looking fellow, well educated comparatively, and as is not unusually the case, he was naturally capable of adapting himself to changed conditions. He did not seem awkward in his good clothes, but appeared as though he had worn fine attire all his life.

At length the hour came when Desmond and Brooks were to part company. The wizard tramp had a sad look upon his face, although he tried to be cheerful and jovial The attempt, however, was a failure. He said:

"I will not go with you to the train, Desmond, we will part here, and you can address your letters to me here; I will arrange to have them forwarded to me in case I go prospecting again."

"You will go prospecting, I suppose, of course."

"I cannot tell; but remember, if anything happens to me I have arranged for you to be communicated with."

There came a look of concern to our hero's face, and the discerning Brooks said:

"You have something to say."

"I have an idea."

"Well?"

"There is great peril in the wilderness."

"Yes."

"There have been cases where men have lost their lives and their deaths have not become known until many years afterward."

"That is true, lad, and I have calculated for that."

"You have?"

"Yes."

"How?"

"You will know if such an event should occur. In the meantime let me tell you if a year should pass and you do not hear from me you will know that I am dead."

"And then?"

"Tell Amy."

"And then?"

"She may make a disclosure to you. Remember, I have taken every precaution."

"I do not know why you should withhold from me your life secret. No harm could come of an immediate revelation, but of course you have your own reasons for withholding your story."

"Yes, that is it, I have reasons; no harm might come of an immediate revelation, but I have reasons of a very satisfactory character to myself. You will understand and appreciate them when they are made known to you. Desmond, I am a changed man; you need have no fear concerning me now; time has righted a wrong. I am strong now—that is, normally strong—all will go well, I believe, if not with me at least with you."

A little later and our hero was on his way across the country to the town where he was to take the train, and a better equipped lad for adventure never boarded a train, and lo, he encountered several very thrilling adventures ere he arrived at the valley farm where kind hearts beat to greet him.

Desmond had been on the train but a few minutes really when he observed a tall, country-looking young fellow, who fixed his eyes on him. As has been demonstrated all through our narrative, Desmond was a very quick, discerning chap; in the language of the day, he was "up to snuff," and the instant he caught the eye of the country-looking fellow he knew that something was up, and he discerned more which will be disclosed as our narrative advances.

Desmond had not boarded a through train; he was to go to a large town where he would meet a through express. The train he had entered was a way train, and he seated himself by the window. No one was in the seat with him at first, but soon the country-looking chap took a seat beside him. The latter appeared to be a jolly, innocent sort of chap, and he addressed the young adventurer with the words:

"Hello!"

There came a merry gleam in Desmond's eyes, as he asked:

"Do you take me for a telephone?"

The stranger arched his eyebrows, and demanded:

"A telephone?"

"Yes."

"What makes you ask that question?"

"Because you yelled 'hello' in my ear."

"I've heard about telephones, but I never saw one."

"You never did?"

"No; what are they like?"

The question was asked seemingly in the most innocent manner, but the keen-witted Desmond's suspicions were at once aroused, and on the instant he made a curious discovery. The fellow was a make-up, under a disguise, and consequently under immediate suspicion also.

"So you never saw a telephone?"

"Never."

"You tell me that?"

"Yes."

Our hero knew he had a long journey before him; he was naturally very fond of a joke and excitement, and besides he had instinctive hatred for designing men. Our hero was aware that the trains, as a rule, are infested with sharps, and the efforts of the railroad companies to squelch these nuisances are not altogether successful. Our adventurer determined to have a little amusement, and if his suspicions were fully verified he was resolved to teach at least one sharp a good lesson. We will repeat, Desmond did not look like an athlete or a youth who had seen the rough side of life; he could easily be mistaken for an ordinarily bright youth who had much to learn.

"So you really never saw a telephone?"

"Never," repeated the man.

Desmond, having determined upon his course of action, assumed a most serious air, and with the greatest earnestness graphically described a telephone, and the stranger appeared to be all interest and attention, and expressed his surprise by innocent ejaculations, as our hero related the wonderful possibilities of the telephone.

It was an amusing scene, or would have been to one who was under the rose and understood that a game was being played.

When Desmond's description apparently, as stated, told in the most earnest manner the sharp, as we shall call him, said:

"Well that beats me, it beats anything I ever heard. See here, stranger, you are making a fool of me with a big fish story because I am a green Western man, born and raised on the prairie."

"No, I've told you the truth."

"Well, well, you come from the city?"

"No, I am going to the city."

"New York?"

"Yes."

"Is that your home?"

"Well, New York lies near where I live."

"Dear me, what wonderful sights you have seen!"

"Yes, sir."

"That New York is a wonderful place."

"You bet it is."

"I am going there some day—yes, I've said I'd see New York some day and I will. It must make a man blind for a few days to go around there."

"Well, yes, it is rather dazzling," said Desmond.

So the conversation continued for quite a time and finally the stranger rose and went away, saying he would return immediately. Quite a respectable-looking man took the vacated seat beside Desmond, and the last neighbor asked:

"Do you know that green-looking chap who was just talking to you?"

"No, sir, I never saw him before."

"Then you don't know who he is?"

"No, sir."

"That is a son of Senator F——, the richest mine owner out in this

Desmond studied the man who was giving him this unsolicited information, and he concluded that the nice-looking man was sharp number two; he was up to this sort of business and perceived the whole game.

"Yes, he appears like a good, honest fellow," said Desmond.

"Honest? why, you could trust him with all you had in the world."

"Yes, he looks that."

"He is one of the kindest-hearted fellows in the world. I tell you if you get into trouble he is the man to aid you. He is the best pistol shot and rifle shot in the land. Why, that fellow has fought off a whole tribe of Indians. The redskins fear him as a white man fears the devil, and his father is one of the richest men out in this section, as I told you."

"Yes. He don't look like a millionaire's son."

"No, but he is all the same, and he appears to have taken a great fancy to you. I was watching him while he talked to you; I tell you no one will interfere with you anywhere in this land if they know that he is your friend."

"That's good."

"Yes. He is a splendid fellow."

The man who had volunteered all this information walked into a forward car, and a few moments later the senator's son, so-called, returned, and as frequently occurs in far Western trains, the particular car in which Desmond was riding was deserted. Our hero and the countryman had the car all to themselves, and after a little further talk the senator's son said:

"I wish some greeny would come in here, we'd have some fun."

"How?"

"I'll tell you, I am a regular juggler; I know all the tricks of gamblers and I'd fool a fellow."

"Do you know all the tricks of gamblers?"

"Yes, and sometimes I beat the game just for fun. You see I am down on gamblers, I just like to beat them. Generally there are one or two of those rascals on this train, but they know me; I don't get a chance at them any more, so I sometimes amuse myself by astonishing greenhorns. By ginger! but it's funny I've never been in New York; I am half a mind to go right on to the great city with you."

"Yes, come along," said Desmond, a merry twinkle in his eyes.

"I can't go, but I'd like to; but you give me your address, and some day you will see me in York. I feel like the man who said, 'See Venice and die;' I want to see New York. Say, they tell me there are a great many sharpers in that wonderful city."

"Yes, it's full of them."

"Well, wouldn't I have fun beating those fellows, especially on the race track, eh? They tell me these sharps are as thick as mosquitoes in August down on the race tracks."

"Yes, they hover around there."

"I like you, young fellow."

"Thank you."

"Yes, I do."

"So you said."

"You're honest; I like an honest young fellow every time. Are you an orphan?"

"A half orphan."

"Your mother dead?"

"No, my father."

"Well, I am just the other way—my mother is dead and my dad, he is away up. They say he is a great man. I reckon he is, but I am no shakes; you see I care more for fun than lands. Now, see here; I'll teach you some tricks. Would you like to learn?"

"Yes, I would."

"Good enough, and when you get back to York you can punish some of those sharps there, for my occupation is gone out here; they won't let me play against them or I'd beat them every time—yes, I beat their game and then give the money away to some poor person who needs it; but they don't know you, and before we get to the end of the route some of those fellows may get aboard, and as I said, they don't know you, and we'll have some great fun; you can beat the game."

"I'd like to do that."

"You would?"

"Yes."

"Why?"

"I was beaten once."

"You were?"

"Yes."

"At what game?"

"Three card monte."

"Well, well! and did they ever come the thimblerig on you?"

"Yes, I had a taste of that also."

"Then you've been through the mill?"

"Yes."

"Well, now, see here; I'll teach you the game, and you are the only one I ever will teach it to; you are honest. But if I were to teach the game to some fellows who claim to be honest they would start in as gamblers right away."

"I never will."

"No, I can see that in your eye; you've got an honest face; I like you clean through."

"Thank you again."

"Yes, and I am going to learn you a trick or two."

"I'll be glad to learn."

The man produced his cards and said:

"I always carry an outfit with me just for fun."

"Is that so?"

"Yes."

"That's fine."

We cannot in words describe the peculiar tones of our hero or the singular expression upon his face, but he was playing for great fun. He held in reserve a great surprise for the senator's son, a grand climax and tableau was to close the scene, or rather, as Desmond classed it in his mind, grand comedy. He did not know just how the fellow intended to work his game; he believed the method would be a novel one, but he was ready—yes, permitting himself to be led on to the grand climax.